They say when life hands you lemons, you should make lemonade.

Or, if you’re IndyCar driver Sarah Fisher, you start your own race team and become one of the leading businesswomen in sports.

The “lemon” that Fisher was dealt came in 2007 in the form of a sour engineer. She already had made a name for herself in the series when in 1999, she became the youngest woman, at 19, to start the Indy 500. She went on to be voted the most popular driver three times.

But in the 2007 season with Dreyer & Reinbold Racing, Fisher struggled because of a car that wasn’t competitive, finishing outside of the top 10 in all but two races. Behind the scenes though, something more troubling was happening.

“That engineer that I was forced to work with was very chauvinistic and didn’t want me in the race car,” Fisher recalled. “He would have rather had any other driver.”

When Fisher offered her input on car adjustments, she was quickly shot down. “He was good at being able to lead our team owner at the time to believe what I was saying was just … female,” she said. “I couldn’t get changes made.” The engineer’s prejudices reached a point where Fisher said she did not even feel safe in the car. “It was just a very bad experience,” she said.

[+] Enlarge

Darrell Ingham/Getty Images

Sarah Fisher practices for the Indianapolis 500 in 2007.

Fisher did not get out of the business, though. She married her husband and crew chief at the time, Andy O’Gara, later that year. It wasn’t long before O’Gara would add “business partner” to his list of associations with Fisher.

“We decided that the only way that we’re going to control who we work with and be able to put the best people together is if we are the team owners,” she said.

Six years later, Fisher is the owner of Sarah Fisher Hartman Racing. She was the first female owner/driver in IndyCar series history and has been mentioned in the same breath as pioneers such as Janet Guthrie and Lyn St. James. Fisher, since retired from driving, has her team headed into this weekend’s Indianapolis 500 with her 22-year-old driver, Josef Newgarden, sitting 13th in points.

And it all started with an opinionated co-worker.

“I would never change that because I’m here today with SFHR because of that,” Fisher said. “It taught me a lot and gave me the courage to jump off and start my own team.”

The road to this point, however, was not always smooth. Her first race for her own team, the 2008 Indy 500, was a struggle. Halfway through, race leader Tony Kanaan crashed into her, eliminating them both from the competition. Running on a small budget funded partially by fan donations, Fisher held back tears as she told ESPN reporter Jamie Little after the crash she was not sure her small team would make it to its next race.

Although she lost a battle that day, she gained a supporter who would be key to the future of her team. Dollar General CEO and avid race fan Rick Dreiling had heard about the fan support and was watching the broadcast when Fisher’s crash caught his attention.

“You could tell she was really trying to get [her team] out of the ground,” Dreiling remembered. “I picked up the phone and called the gentleman who was running our racing program at the time.”

Dollar General soon became the primary sponsor for SFHR, and Dreiling became a friend to Fisher. As time went on and SFHR grew, Dreiling said Fisher’s passion for the sport and skills in business were evident.

“Sarah has a very solid business head about her. She knows how to manage that team,” Dreiling said. “I think that’s part of the reason she and I got along so well together. We spent more time talking about business than we did about car racing. I used to kid her on that: ‘I came here to watch you go 200 miles per hour, not talk about Dollar General.’ ”

It took Fisher a little longer to realize her talent for management. “It was very tough to be both an athlete and a CEO and entrepreneur at the same time. Each one, to do very well, takes a lot,” she said. “After working with Josef Newgarden and seeing that, I don’t know how the heck I pulled that off.”

Fisher did it for three years. But near the end of 2010, she had a growing desire to tackle yet another responsibility — being a mom. “In the back of my mind I was thinking, ‘I want to have a family.’ And a female athlete can’t do that and be an athlete at the same time,” Fisher said.

Fisher decided it was time to trade in the fire suit for motherhood. Dreiling again provided the support she needed. She approached him in November 2010 to tell him she wanted to turn the driving responsibilities over to someone else; he did not hesitate to continue supporting the team. “I was incredibly happy for Sarah,” said Dreiling, who was pleased she planned to continue running SFHR. “I was afraid she was going to get out of the business.”

Fisher announced her retirement in late 2010, and a month later, she was pregnant.

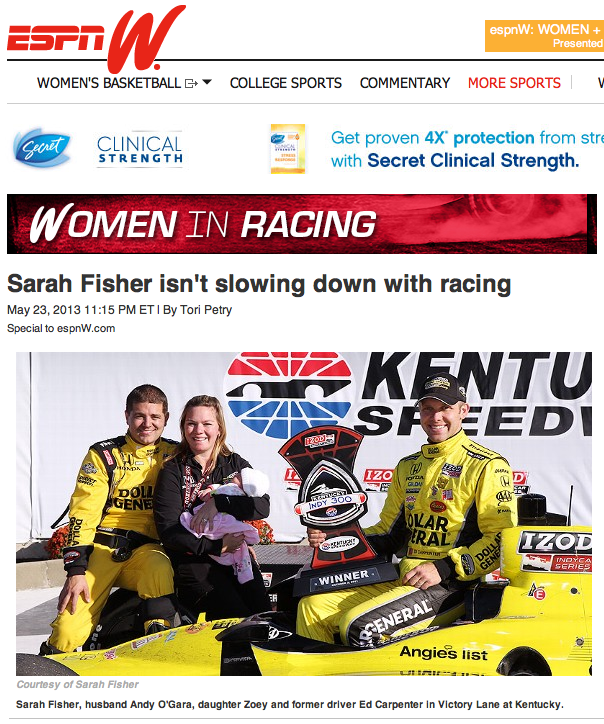

In September 2011, her daughter, Zoey, was born. Just three weeks later, her young race team brought home its first win, at Kentucky Speedway with Ed Carpenter behind the wheel. Both Dreiling and 3-week-old Zoey were there to witness the win alongside Fisher. It was in that moment that Fisher knew transitioning to team owner was the right choice.

[+] Enlarge

Courtesy of Sarah Fisher

Although Dollar General is no longer a sponsor with Sarah Fisher Hartman Racing, its CEO and avid racing fan Rick Dreiling is confident in the team’s future and says Fisher is a pioneer.

“When everybody there at Kentucky was standing in Victory Lane, that was like, ‘Yes, we are doing the right thing, and this is exactly what we want to do going forward,’ ” Fisher said.

Life outside of the driver’s seat has not slowed down. “It’s a lot more work now,” Fisher admitted. “Balancing time is still one of those things I’m learning about, and I think I’ll be learning about ’til the day I die.”

Not only is she the CEO of a 23-person enterprise running a full IndyCar season, but she is also a member of the National Women’s Business Council, an advisory panel to the U.S. president and Congress on women’s business issues. Two years ago, she was chosen to represent women in the entertainment and sporting industry on the council, and now she participates in research initiatives to help discover ways to expand the number of women in business in the United States. “I want to be able to contribute enough to the council that makes a difference in opportunities that women have,” she said. “Regardless of the industry you’re in, it is achievable to have your own business as a female. I’m in a very, very, very male-dominated industry that’s public, so people are very aware of it. I hope that helps the council and the awareness of females in business.”

As far as coming across any more unpleasant characters like the one who propelled her to her current status? Fisher said never. “I never once ran into any type of that, from a peer standpoint, or from a driver standpoint,” she said. “Except for this one little engineer.”

In fact, she believes that she has been well-respected throughout her time in IndyCar. “I always had good support because of performance,” she said. “If you perform, then it’s an obvious acceptance and support.”

Although he is no longer a sponsor of SFHR, Dreiling has no doubt she will continue to perform.

“I consider Sarah to be a pioneer,” he said. “I can’t think of anyone that I think that would be more capable of breaking the final barrier of IRL team ownership than Sarah. It is a natural progression for her.

“Once this chapter in her racing career is written, I think we’re going to be really, really proud of her and really excited about what she’s accomplished.”

There’s a sour engineer somewhere to thank for it.

Tori wrote this story for espnW as part of a 5-story series on women in racing in the week leading up to the Indy 500 and Coke 600. You can find the original story here.